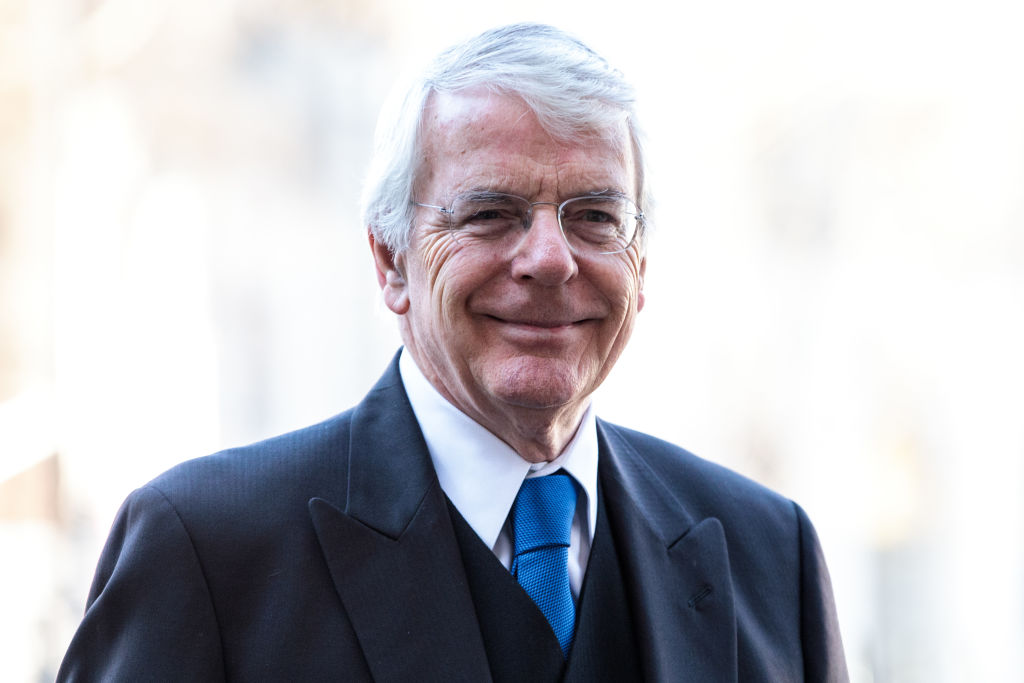

LONDON — By any standards it has been a miserable start for Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain, who stands accused of subverting the country’s unwritten constitution and has yet to win a vote in Parliament.

Lawmakers have twice rejected his call for an election, and have passed legislation that upended his strategy for exiting the European Union on Oct. 31 “do or die.”

Yet his Conservative Party enjoys a healthy opinion-poll lead over the opposition Labour Party, his personal ratings well exceed those of Labour’s leader, Jeremy Corbyn, and they have increased several percentage points since Mr. Johnson came to power two months ago. In light of that apparent paradox, some analysts see his unorthodox style and communication skills as setting him on the road to electoral victory.

“I think what we are seeing is a bit like Donald Trump in the U.S., where those who dislike Boris Johnson see confirmation in what he does of how appalling he is, whereas those better disposed to him are willing to discount all manner of things,” said Roger Awan-Scully, head of politics and international relations at the University of Cardiff.

After three years of slow political convulsions, Brexit has reordered British politics to such an extent that almost everything is now refracted through voter perceptions of that issue.

And in this polarizing context, Mr. Johnson seems to be presenting himself as the man who will deliver Brexit despite the opposition of lawmakers and the establishment, limbering up for a “people against Parliament” campaign.

“We are seeing everything through Brexit lenses,” said Mr. Awan-Scully. This tendency, he said, may break well for the Conservatives in a general election that most analysts considered inevitable.

Sara Hobolt, a professor at the London School of Economics, goes further, describing a Conservative majority as the “most likely outcome” of the next general election, “if the vote splits the right way.”

That is remarkable given accusations that Mr. Johnson has undermined democracy by sending Parliament away for five weeks and split his own party by banishing 21 Tory lawmakers over Brexit, a move that compelled his own brother, Jo, to quit the government.

Even his trademark presentational skills have abandoned Mr. Johnson — for example during a bumbling speech to a group of police cadets (one of whom came close to fainting behind him), or when faced by voters who plainly dislike him.

When confronted by the father of a sick child in a hospital on Wednesday, Mr. Johnson denied that the visit was a publicity stunt, insisting that there was no press anywhere nearby. Then his interlocutor pointed to a television crew, which had captured an awkward prime minister in the act of uttering an evident untruth.

But just as Mr. Trump appeals to core supporters, Mr. Johnson’s tough stance on Brexit has won over voters determined to leave the bloc. Doubling down on that base helps him draw support from the Brexit Party that won the European elections in Britain this year, just weeks after the party had been created by the populist campaigner, Nigel Farage.

If that sounds like a move from Mr. Trump’s playbook, British voters were warned last year, by Mr. Johnson, that it might happen.

“Imagine Trump doing Brexit,” Mr. Johnson said in private comments that were recorded and leaked. ”He’d go in bloody hard. There’d be all sorts of breakdowns, all sorts of chaos. Everyone would think he’d gone mad. But actually you might get somewhere. It’s a very, very good thought.”

Like Mr. Trump, Mr. Johnson defies many of the normal rules of politics, laughing off setbacks and ignoring questions he would rather not answer. (He has, for example, never said publicly how many children he has fathered.)

Some political pollsters say Mr. Johnson’s relative success may say more about the nation he leads than about him.

“You are not talking about one country, it is two, made up of Remain supporters and Brexit supporters and they usually disagree over just about everything,” said John Curtice, a professor at the University of Strathclyde and Britain’s most respected polling expert.

By historical standards, Mr. Johnson is not particularly popular for a new prime minister, said Mr. Curtice, but in a society polarized by Brexit, he is a “Marmite politician” — referring to the thick yeasty paste that Britons love or loathe.

YouGuv, a London-based polling concern, said Conservatives have nearly doubled their voter preference rating compared with three months ago to 32 percent, around nine percentage points ahead of Labour.

Asked in one YouGuv survey who would be the best prime minister, Mr. Johnson scored 38 percent among respondents, while Mr. Corbyn scored 22 percent (lower even than Mr. Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, who scored 29 percent in June.)

“Boris Johnson’s reputation among leavers is simply reinforced by recent developments — and similarly among Remainers,” Mr. Curtice said.

That was illustrated on Monday in Luxembourg when, greeted by a small group of protesters, Mr. Johnson skipped a news conference with the Luxembourg prime minister, Xavier Bettel, who proceeded without him and blamed the British for the Brexit “mess.”

Just before the meeting Mr. Johnson compared Britain’s efforts to escape the European Union to the adventures of the Incredible Hulk, the Marvel superhero. So, when he withdrew from the news conference, critics christened Mr. Johnson the “incredible sulk.” But Brexit supporters saw a continental leader victimizing their man. (“Luxembourg laughs in Johnson’s face” was the banner headline in the pro-Brexit Daily Telegraph.)

According to his supporters, such events further cement Mr. Johnson in the public mind as “Mr. Brexit,” helping him to marginalize Mr. Farage and cannibalize support from his insurgent Brexit Party.

Mr. Awan-Scully said that, by uniting the pro-Brexit right, Mr. Johnson could win enough of a fragmented electorate for election victory. Britain’s electoral system operates on a winner-take-all basis, so divisions among his opponents could allow Mr. Johnson a path.

But Mr. Curtice expressed caution that Mr. Johnson’s core vote might not be enough.

“He’s loved by Leavers and almost universally disliked by those who voted Remain. So he only has about 50 percent of the population that he can appeal to,” said Mr. Curtice. “Half the country dislikes him and he does not seem to be certain in his public performances, so we are wondering how this is going to pan out.”

The Conservative lead over the Labour Party probably says more about the opposition’s weakness than the government’s strength, and illustrates the scramble for votes on both sides of the Brexit divide.

While Mr. Johnson is battling with Mr. Farage, Mr. Corbyn is in a fight with the newly revived centrist and pro-European Liberal Democrats under the leadership of Jo Swinson.

“The competition is not between Johnson and Corbyn, it’s between Johnson and Farage on the one hand, and Corbyn and Swinson on the other,” Mr. Curtice said. “The reason Johnson is ahead is not because he has squeezed the Labour vote, it’s because he has squeezed the Brexit Party.”

So Mr. Johnson’s prospects may depend largely on whether he can continue to do that as Brexit reaches another decisive moment.

Having promised repeatedly to leave the bloc on Oct. 31, Mr. Johnson is hemmed in. Parliament has passed a law requiring him to request another delay if he cannot get a new Brexit agreement — and a deal with Brussels still remains a long shot.

If Mr. Johnson fails to deliver Brexit, or compromises too much in the eyes of pro-Brexit Britons, Mr. Farage will be on the attack again, crying betrayal, Mr. Curtice said. Such an outcome would be ominous for the Tories and their leader.

“The $64,000 question is can he deliver and what can he deliver?” Mr. Curtice said. “If he can’t get an agreement and can’t get no-deal through Parliament the question will be: ‘Is this any more than a joke?’”

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/world/europe/boris-johnson-brexit-polls.html

2019-09-20 09:00:00Z

CAIiECrTFwAjSWB8RsiO9Tks7qwqFwgEKg8IACoHCAowjuuKAzCWrzwwt4QY